the system was built this way

how do I reconcile my relationship between God, Truth, and religion?

This essay was inspired by a photo I took two years ago, along with a prompt from the writing collective I’m a part of at Foster. In our upcoming Season, we’re exploring what it means to inhabit a “more beautiful question.” As Rilke said, we’re drawn towards loving and living the questions that matter to us, rather than stressing over definitive answers.

The past three years have been me inhabiting some big questions around my relationship to Christianity. There was so much resistance for me to share and talk about this. But being a part of Foster and hearing so many other people grapple with their unanswerable questions pushed me over the edge to share mine.

If you’re interested in discovering and inhabiting your own beautiful question together, our season starts on October 16th, and applications close on the 13th.

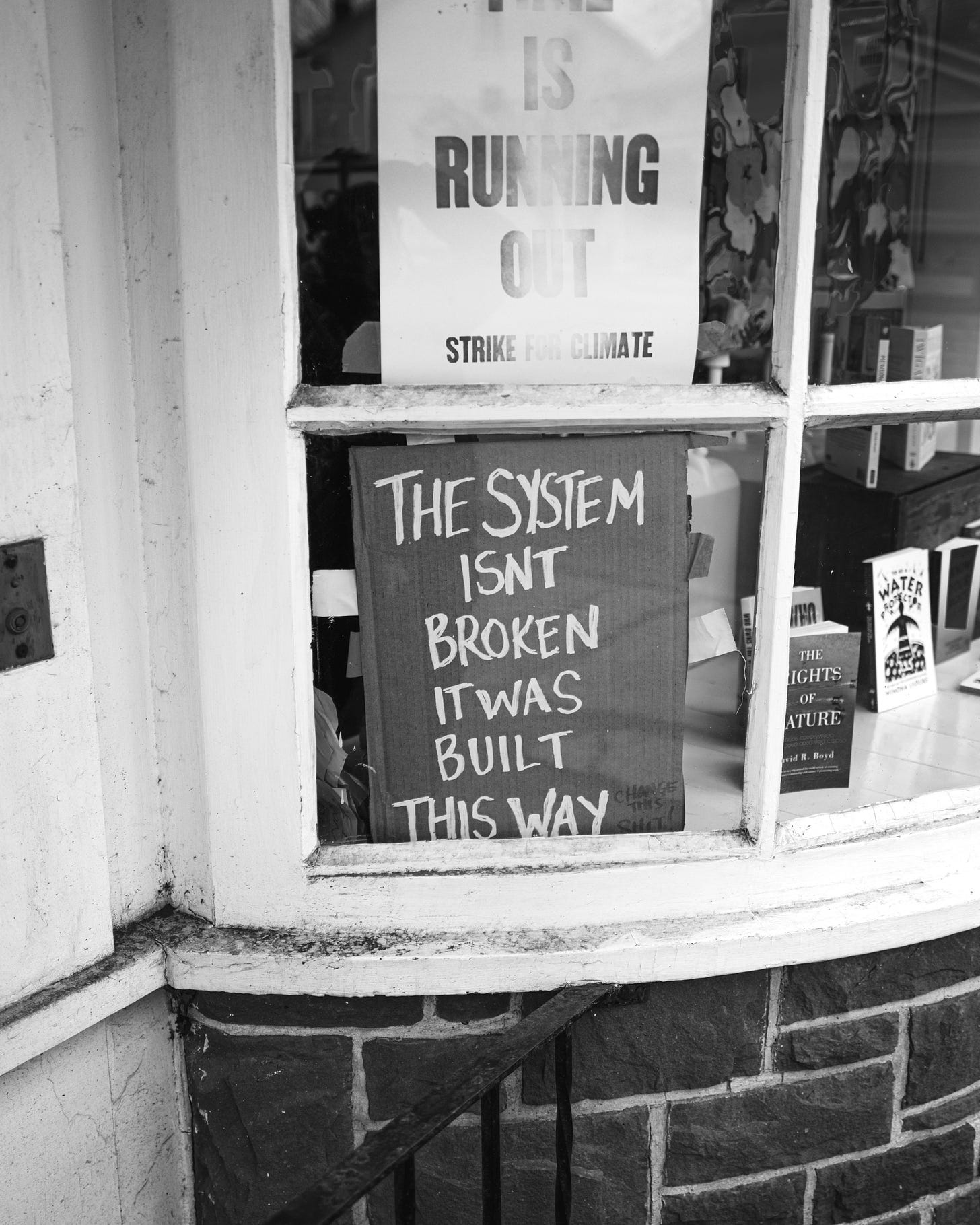

I took this photo in upstate New York, where a few friends and I went to welcome the new year at the end of 2021. The trip was a milestone after everything that happened the past two years: the lockdowns in 2020, George Floyd’s murder, the protests and reckoning afterwards.

The reckoning I went through brought up questions that challenged the religious system I was a part of as a Christian. Questions I didn’t have the courage to ask because I didn’t want to suffer the consequences. One of those being earlier that year, I left the church I attended for close to a decade. I was there when the church first started and was the closest community I was a part of until then. It made no sense that I was choosing to leave when there was no tragedy or falling out that had caused it. But the falling out was more within me as I was deconstructing the faith I had believed in my entire life.

Growing up in the church, I learned that questioning any of the beliefs we held onto was a hazardous thing to do. Genuine curiosity was seen as genuine doubt, and God forbid I questioned a faith that held God, Truth and religion were the same thing.

In order to fit in and make sure I got to heaven, I suppressed any doubt and just believed. And I really did believe, and still do believe the central tenets of my Christian faith, but I don’t think getting here had to feel so dangerous and sinful. Because back then, I didn’t know I needed a safe space to be seen and heard for who I was and what was coming up for me. I didn’t know I needed empathy—for someone to sit with me and wrestle through questions about my faith and how it fits in with the world, not told to just pray more and memorize Bible verses.

What I really didn’t know was that the people I was looking to didn’t know how to hold that safe space for themselves. The pressure to not question my faith was the same pressure they put on themselves. They were just as confused, afraid, and lonely as I was, and religion was there for comfort and some kind of status, not for growth and transformation. Leaving my church that year was my way of giving myself what I needed as I sat with the unanswerable question of how I could reconcile my relationship between God, Truth, and religion.

God, until then, was only seen through the lens of Christian reformed theology. A theology that has a long tradition of scholarship and teaching on specific truths about who God is and what He is doing in the world. That tradition was the foundation of the religion I was born into. It had grounded me with a fundamental certainty in an uncertain world, but now that same orthodoxy felt limiting and constricting. I once heard a podcast someone say, "God is the blanket we put over the mystery to give it a shape." These days, my relationship with Mystery and its endless discoveries feel more certain than the theological truths I used to study or debate over.

The function of healthy religion is to “re-ligio”—to re-ligament or re-align us with what really matters. But in the wake of my reckoning with white supremacy and as a person of color, I saw how people used religion to project dehumanizing prejudices against “unbelievers” and “sinners.” I saw what poisoned religion looked like: one built not to align us, but divide us from one another. A system that championed power, status, and ego, not faith, hope, and love.

The photo reminded me that there were others who were asking the same questions. Questions that aren’t meant to be answered rather teach us to “be patient toward all that is unsolved” and to “try to love the questions themselves,” as Rilke would say. Asking the questions, wrestling with them, and writing about them is the way to find others and feel less alone. I’m shedding the guilt of doubting what I once held to be true. I’m realizing asking questions isn’t an act of rebellion but a sign of growth.

And when it comes to this faith tradition I have reclaimed and still hold dear, these questions are leading me somewhere cosmic, somewhere much larger than the straight and narrow certainty I was taught to believe.

every journey is different, but i can relate to the major strands here!

Brave and bold. Loved the wee linguistics interlude too.